Quick Summary

- New ruling from the Supreme Court looms large

This appeared at , a nonprofit news site covering education. to get more like this in your inbox.

Updated July 14

The Supreme Court on Monday allowed Education Secretary Linda McMahon to move ahead with firing more than 1,300 employees at the U.S. Department of Education as the Trump administration aims to eliminate the federal agency.

While the states that sued and the governmentās lawyers will continue to argue the case in the lower courts, McMahon said the opinion shows that the president āhas the ultimate authority to make decisions about staffing levels, administrative organization and day-to-day operations of federal agencie²õ.ā

Justice Sonia Sotomayor, joined by Justices Ketanji Brown Jackson and Elena Kagan, dissented with the ruling.

āAs Congress mandated, the department plays a vital role in this nationās education system, safeguarding equal access to learning and channeling billions of dollars to schools and students across the country each year,ā Sotomayor wrote. āWhen the executive publicly announces its intent to break the law, and then executes on that promise, it is the judiciaryās duty to check that lawlessness, not expedite it.ā

When a white teacher at Decatur High School used the , students walked out and marched in protest. But Reyes Le wanted to do more.

Until he graduated from the Atlanta-area school this year, he co-led its equity team. He organized walking tours devoted to Decaturās history as a thriving community of freed slaves after the Civil War. Stops included a statue of civil rights leader , which replaced a Confederate monument, and a historical marker recognizing the site where Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. was for driving with an out-of-state license.

Reyes Le, a Decatur High graduate, sits at the base of Celebration, a sculpture in the townās central square that honors the cityās first Black commissioner and mayor. (Linda Jacobson/The 74)

Reyes Le, a Decatur High graduate, sits at the base of Celebration, a sculpture in the townās central square that honors the cityās first Black commissioner and mayor. (Linda Jacobson/The 74)

But Le feared his efforts would collapse in the face of the Trump administrationās crackdown on diversity, equity and inclusion. An existing state law against ādivisive conceptsā meant students already had to get parent permission to go on the tour. Then the district threw out two non-discrimination policies April 15.

āI felt that the work we were doing wouldnāt be approved going into the future,ā Le said.

Kevin Gee, an education researcher at the 51³Ō¹Ļ±¬ĮĻĶų, Davis, had to stop his research work when the Trump administration cancelled grants.

Decatur got snared by the U.S. Department of Educationās to pull millions of dollars in federal funding from states and districts that employed DEI policies. In response, several organizations sued the department, calling its guidance vague and in violation of constitutional provisions that favor local control. Within weeks, three federal judges, including one Trump appointee, Education Secretary Linda McMahon from enforcing the directives, and Decatur promptly .

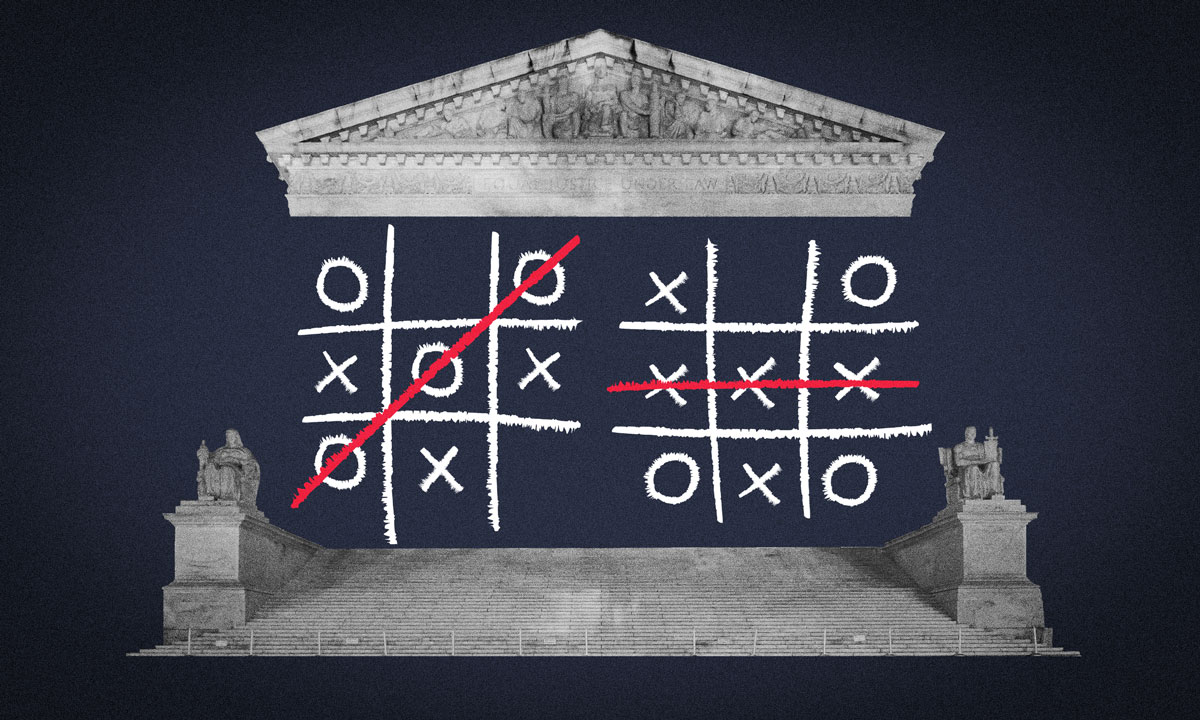

The reversal offers a glimpse into the courtsā role in thwarting ā or at least slowing down ā the Trump education juggernaut. States, districts, unions, civil rights groups and parents sued McMahon, and multiple courts the department skirted the law in slashing funding and staff. But some observers say the administration is playing a long game and may view such losses as temporary setbacks.

āThe administrationās plan is to push on multiple fronts to test the boundaries of what they can get away with,ā said Jeffrey Henig, a professor emeritus of political science and education at Teachers College, Columbia University. āCut personnel, but if needed, add them back later. Whatās gained? Possible intimidation of ādeep stateā employees and a chance to hire people that will be āa better fit.ā ā

A recent example of boundary testing: The administration nearly $7 billion for education the president already approved in March.

But the move is practically lifted from the pages of , the right-wing blueprint for Trumpās second term. In that document, Russ Vought, now Trumpās director of the Office of Management and Budget, argues that presidents must āhandcuff the bureaucracyā and that the Constitution for the White House to spend everything Congress appropriated.

The administration blames Democrats for playing the courts. White House Deputy Chief of Staff Stephen Miller āradical rogue judgesā of getting in the presidentās way.

The end result is often administrative chaos, leaving many districts unable to make routine purchases and displaced staff unsure whether to move on with their lives.

While the outcome in the lower courts has been mixed, the Supreme Court ā which has on much of Trumpās agenda ā is expected any day to weigh in on the presidentās biggest prize: whether McMahon can permanently cut half the departmentās staff.

In that case, 21 Democratic attorneys general and coalition of districts and unions sued to prevent the administration from taking a giant step toward eliminating the department.

āEverything about defunding and dismantling by the administration is in judicial limbo,ā said Neal McCluskey, director of the libertarian Cato Instituteās Center for Educational Freedom. As a supporter of eliminating the department, he lamented the āIf the Supreme Court allows mass layoffs, though, I would expect more energy to return to shrinking the department.ā

The odds of that increased last week when the that mass firings at other agencies could remain in effect as the parties argue the case in the lower courts.

While the lawsuits over the Education Department are separate, Johnathan Smith, chief of staff and general counsel at the National Center for Youth Law, said the ruling is āclearly not a good sign.ā His case, filed in May, focuses on cuts specifically to the departmentās Office for Civil Rights, but the argument is essentially the same: The administration overstepped its authority when it gutted the department without congressional approval.

Solicitor General John Sauer, in to the Supreme Court, said the states had no grounds to sue and called any fears the department couldnāt make do with a smaller staff merely āspeculative.ā

Education Secretary Linda McMahon defended her cuts to programs and staff before a House education committee June 4. (Sha Hanting/China News Service/VCG via Getty Images)

Education Secretary Linda McMahon defended her cuts to programs and staff before a House education committee June 4. (Sha Hanting/China News Service/VCG via Getty Images)

Even if the Supreme Court rules in McMahonās favor, its opinion wonāt affect previous rulings and other lawsuits in progress against the department.

Hereās where some of those key legal battles stand:

COVID relief funds

McMahon stunned states in when she said they would no longer receive more than $2 billion in reimbursements for COVID-related expenses. States would have to make a fresh case for how their costs related to the pandemic, even though the department had already approved extensions for construction projects, summer learning and tutoring.

On June 3, a federal judge in Maryland from pulling the funds.

Despite the judicial order, not all states have been paid.

The Maryland Department of Education still had more than $400 million to spend. Cherie Duvall-Jones, a spokeswoman, said the agency hasnāt received any reimbursements even though it provided the ānecessary documentation and informationā federal officials requested.

The cancellation forced Baltimore City schools to dip into a to avoid disrupting tutoring and summer school programs.

Madison Biedermann, a spokeswoman for the department, declined to comment on why it had yet to pay Maryland or how much the department has distributed to other states since June.

Mass firings

In the administrationās push to wind down the department, McMahon admits she still needs staff to complete what she calls her āfinal mission.ā On May 21, she told a House appropriations subcommittee that she had rehired 74 people. Biedermann wouldnāt say whether that figure has grown, and referred a reporter to the .

āYou hope that youāre just cutting fat,ā McMahon testified. āSometimes you cut a little in the muscle.ā

The next day, a federal district court her to also reinstate the more than 1,300 employees she fired in March, about half of the departmentās workforce. Updating the court on progress, Chief of Staff Rachel Oglesby said in a that sheās still reviewing survey responses from laid off staffers and figuring out where they would work if they return.

Student protestors participate in the āHands Off Our Schoolsā rally in front of the U.S. Department of Education on April 4 in Washington, D.C. (Getty Images)

Student protestors participate in the āHands Off Our Schoolsā rally in front of the U.S. Department of Education on April 4 in Washington, D.C. (Getty Images)

But some call the departmentās to bring back employees lackluster, perhaps because itās pinning its hopes on a victory before the Supreme Court.

āThis is a court thatās been fairly aggressive in overturning lower court decisions,ā said Smith, with the National Center for Youth Law.

His groupās lawsuit is one of two challenging cuts to the Office for Civil Rights, which lost nearly 250 staffers and seven regional offices. They argue the cuts have left the department unable to thoroughly investigate complaints. Of the 5,164 civil rights complaints since March, OCR has dismissed 3,625, Oglesby .

In a case brought by the Victim Rights Law Center, a Massachusetts-based advocacy organization, a federal district court McMahon to reinstate OCR employees.

Even if the case is not reversed on appeal, thereās another potential problem: Not all former staffers are eager to return.

āI have applied for other jobs, but Iād prefer to have certainty about my employment with OCR before making a transition,ā said Andy Artz, who was a supervising attorney in OCRās New York City office until the layoffs. āI feel committed to the mission of the agency and Iād like to be part of maintaining it if reinstated.ā

DEI

An aspect of that mission, nurtured under the Biden administration, was to discourage discipline policies that result in higher suspension and expulsion rates for minority students. A warned that discrimination in discipline could have ādevastating long-term consequences on students and their future opportunitie²õ.ā

But according to the departmentās , efforts to reduce those gaps or raise achievement among Black and Hispanic students could fall under its definition of āimpermissibleā DEI practices. Officials demanded that states sign a form certifying compliance with their interpretation of the law. On April 24, three federal courts ruled that for now, the department canāt pull funding from states that didnāt sign. The department also had to temporarily designed to gather public complaints about DEI practices.

The cases, which McMahon has asked the courts to dismiss, will continue through the summer. In court records, the administrationās lawyers say the groupsā arguments are weak and that districts like Decatur simply overreacted. In an example cited in a complaint brought by the NAACP, the Waterloo Community School District in Iowa responded to the federal guidance by of a statewide āread-Inā for Black History Month. About 3,500 first graders were expected to participate in the virtual event featuring Black authors and illustrators.

The department said the move reflected a misunderstanding of the guidance. āWithdrawing all its students from the read-In event appears to have been a drastic overreaction by the school district and disconnected from a plain reading of the ā¦ documents,ā the department said.

Desegregation

The administrationās DEI crackdown has left many schools confused about how to teach seminal issues of American history such as the Civil Rights era.

It was the Civil Rights Act of 1964 that established ādesegregation centersā across the country to help districts implement court-ordered integration.

In 2022, the Biden administration awarded $33 million in grants to what are now called equity assistance centers. But Trumpās department views such work as inseparable from DEI. When it cancelled funding to the centers, it described them as āwokeā and ādivisive.ā

Judge Paul Friedman of the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia, a Clinton appointee, disagreed. He blocked McMahon from pulling roughly $4 million from the Southern Education Foundation, which houses Equity Assistance Center-South and helped finance Brown v. Board of Education over 70 years ago. His order referenced President Dwight Eisenhower and southern judges who took the ruling seriously.

āThey could hardly have imagined that some future presidential administration would hinder efforts by organizations like SEF ā based on some misguided understanding of ādiversity, equity, and inclusionā ā to fulfill Brownās constitutional promise to students across the country to eradicate the practice of racial segregation.ā

He said the center is likely to win its argument that canceling the grant was āarbitrary and capriciou²õ.ā

Raymond Pierce, Southern Education Foundation president and CEO, said when he applied for the grant to run one of the centers, he emphasized its historical significance.

āMy family is from Mississippi, so I remember seeing a ācoloredā entrance sign on the back of the building as we pulled into my motherās hometown for the holidays,ā Pierce said.

Trumpās Justice Department many of the remaining 130 desegregation orders across the South. Harmeet Dhillon, assistant attorney general for civil rights, has said the orders force districts to spend money on monitoring and data collection and that itās time to for past discrimination.

But EshƩ Collins, director of Equity Assistance Center-South, said the centers are vital because their services are free to districts.

āSome of these cases havenāt had any movement,ā she said. āDistricts are like āWell, we canāt afford to do this work.ā Thatās why the equity assistance center is so key.ā

EshƩ Collins, director of Equity Assistance Center-South and a member of the Atlanta City Council, read to students during a visit to a local school. (Courtesy of EshƩ Collins)

EshƩ Collins, director of Equity Assistance Center-South and a member of the Atlanta City Council, read to students during a visit to a local school. (Courtesy of EshƩ Collins)

Her center, for example, works with the in Tennessee to recruit more Black teachers and ensure minority students get an equal chance to enroll in advanced classes. The system is still under a desegregation order from 1965, but is on track to meet the terms set by the court next year, Collins said. A week after Friedman issued the injunction in the foundationās case, Ruth Ryder, the departmentās deputy assistant secretary for policy and programs, told Collins she could once again access funds and her work resumed.

Research

As they entered the Department of Education in early February, one of the first moves made by staffers of the Department of Government Efficiency was to terminate nearly $900 million in research contracts awarded through the Institute for Education Sciences. Three lawsuits say the cuts seriously hinder efforts to conduct high-quality research on schools and students.

Kevin Gee from the 51³Ō¹Ļ±¬ĮĻĶų, Davis, was among those hit. He was in the middle of producing a practice guide for the nation on chronic absenteeism, which continues to exceed pre-pandemic levels in all states. In a , the American Enterprise Instituteās Nat Malkus said the pandemic ātook this crisis to unprecedented levelsā that āwarrant urgent and sustained attention.ā Last yearās rate stood at ā still well above the 15% before the pandemic.

Gee was eager to fully grasp the impact of the pandemic on K-3 students. Even though young children didnāt experience school closures, many missed out on preschool and have in social and academic skills.

Westat, the contractor for the project, employed 350 staffers to collect data from more than 860 schools and conduct interviews with children about their experiences. But DOGE halted the midstream ā after the department had already invested about $44 million of a $100 million contract.

Kevin Gee, an education researcher at the 51³Ō¹Ļ±¬ĮĻĶų, Davis, had to stop his research work when the Trump administration cancelled grants. (Courtesy of Kevin Gee)

Kevin Gee, an education researcher at the 51³Ō¹Ļ±¬ĮĻĶų, Davis, had to stop his research work when the Trump administration cancelled grants. (Courtesy of Kevin Gee)

āThe data wouldāve helped us understand, for the first time, the educational well-being of our nationās earliest learners on a nationwide scale in the aftermath of the pandemic,ā he said.

The department has no plans to resurrect the project, according to a June . But there are other signs it is walking back some of DOGEās original cuts. For example, it intends to reissue contracts for regional education labs, which work with districts and states on school improvement.

āIt feels like the legal pressure has succeeded, in the sense that the Department of Education is starting up some of this stuff again,ā said Cara Jackson, a past president of the Association for Education Finance and Policy, which filed one of the lawsuits. āI think ā¦ thereās somebody at the department who is going through the legislation and saying, āOh, we actually do need to do this.ā ā

Mental health grants

Amid the legal machinations, even some Republicans are losing patience with McMahonās moves to freeze spending Congress already appropriated.

In April, she terminated $1 billion in mental health grants approved as part of a 2022 law that followed the mass school shooting in Uvalde, Texas. The department told grantees, without elaboration, that the funding no longer aligns with the administrationās policy of āprioritizing merit, fairness and excellence in educationā and undermines āthe students these programs are intended to help.ā

The secretary told Oregon Democratic Sen. Jeff Merkley in June that she would the grants, but some schools donāt want to wait. Silver Consolidated Schools in New Mexico, which lost $6 million when the grant was discontinued, sued her on June 20th. Sixteen Democrat-led states filed a second later that month.

The funds, according to , allowed it to hire seven mental health professionals and contract with two outside counseling organizations. With the extra resources, the district saw bullying reports decline by 30% and suspensions drop by a third, according to the districtās complaint. Almost 500 students used a mental health app funded by the grant.

A judge has yet to rule in either case, but Republican Rep. Brian Fitzpatrick of Pennsylvania and other members of a bipartisan task force are that sheāll open a new competition for the funds.

āThese funds were never intended to be a theoretical exercise ā they were designed to confront an urgent crisis affecting millions of children,ā Fitzpatrick said in a statement. āWith youth mental health challenges at an all-time high, any disruption or diversion of resources threatens to reverse hard-won progress and leave communities without critical support²õ.ā